You can calculate a correlation coefficient but can’t tell if a marketing claim makes sense. You’ve memorized optimization formulas but freeze when deciding how to allocate your budget. This disconnect between computational skills and practical reasoning reveals a fundamental problem: traditional mathematical education teaches procedures while life demands analytical judgment.

Mathematical competency involves developing four key analytical capabilities: statistical interpretation, probability reasoning, mathematical modeling, and optimization thinking. These capabilities serve as decision-making frameworks that are cultivated through systematic engagement with authentic problems. Readers will gain an understanding of these competencies, where they manifest, why traditional approaches often fall short, and what effective frameworks exist for building practical mathematical reasoning.

The Four Competencies of Mathematical Reasoning

Statistical interpretation helps you evaluate evidence properly. You’ll assess claims, spot methodological problems, and catch misleading data presentations. It’s about questioning what the numbers actually support versus what someone claims they support. This skill matters when you’re interpreting polls, studies, or any statistical information thrown at you in media and marketing.

Probability reasoning lets you assess risk by putting numbers on uncertainty. You can compare different outcomes and make decisions when you don’t have complete information. Instead of thinking in black and white, you’ll weigh likelihood against consequences. Think insurance decisions or evaluating investment risks.

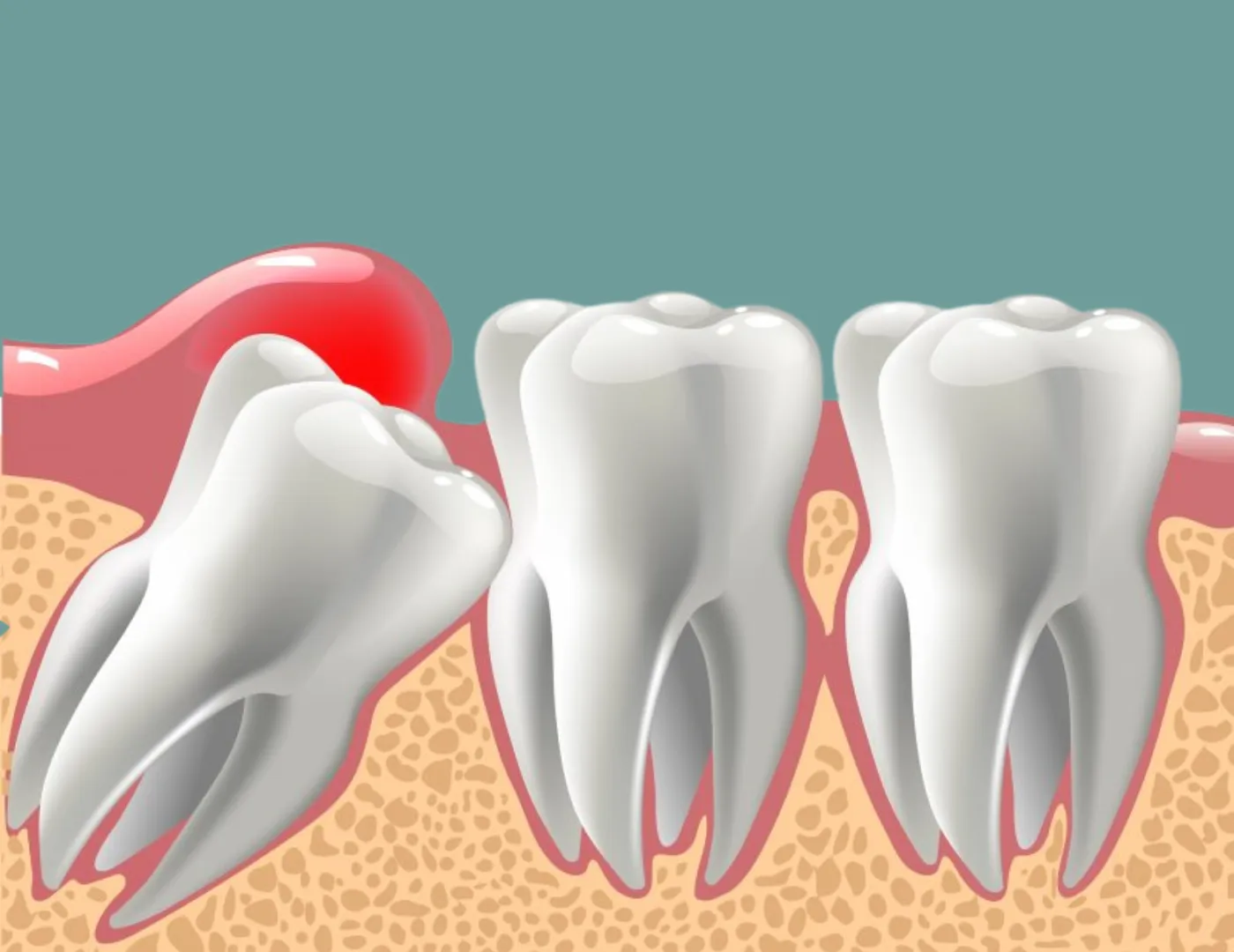

Mathematical modeling helps you understand systems by mapping out relationships and spotting key variables. Complex situations become manageable when you abstract the essential patterns from all the noise. You can predict how changes ripple through connected parts. It’s vital for grasping complex behaviors and forecasting outcomes.

Optimization thinking drives smart resource allocation. You’ll identify constraints and evaluate trade-offs systematically. Vague improvement goals become concrete approaches for maximizing results.

These competencies focus on ‘what to evaluate’ and ‘how to reason’ rather than ‘how to calculate.’ They’re thinking frameworks, not just computational procedures.

Actually, here’s what’s interesting: most people already use these frameworks informally when they compare insurance policies or figure out the fastest route to work. The challenge isn’t learning to think mathematically—it’s recognizing when you’re already doing it.

Transferable Frameworks Across Decision Contexts

Statistical interpretation manifests across various contexts. Professionals use it to evaluate business performance metrics and market research data, individuals assess health information and financial product comparisons, and citizens evaluate policy effectiveness claims and research findings in media. Despite different subject matter, the same analytical framework—questioning what conclusions data actually supports—transfers across contexts.

Probability reasoning is evident in professionals assessing risk in project planning and investment decisions, individuals evaluating insurance needs and comparing uncertain financial outcomes, and citizens considering policy trade-offs involving probabilistic benefits and risks. The capability to quantify and compare uncertain outcomes remains constant while specific decisions vary.

Mathematical modeling finds applications in managers analyzing organizational dynamics and predicting operational outcomes, individuals understanding how spending patterns affect long-term financial goals, and citizens evaluating how policy changes cascade through complex social systems. The modeling competency applies regardless of the system being modeled.

Optimization thinking is used by professionals allocating limited resources across competing priorities, individuals balancing financial goals against budget constraints and time limitations, and citizens evaluating public resource deployment. The same mathematical competency enables different decisions across contexts, suggesting transferable analytical frameworks provide more value than domain-specific techniques.

The Development Challenge in Traditional Instruction

Traditional math instruction focuses on deriving procedures, proving theorems, and solving closed-form problems with predetermined solutions. Students learn to calculate statistical measures without interpreting what they reveal. They compute probabilities without assessing real risks. They solve optimization problems without identifying what should be optimized. Teachers show computational procedures, but analytical frameworks stay hidden.

It’s like teaching someone to use a calculator without explaining when multiplication might be useful.

Students master the mechanics but miss the point entirely. Skills developed through abstract exercises don’t transfer to authentic contexts because students never learn to recognize when mathematical frameworks apply to messy real-world situations. Recognizing that a business decision involves optimization? That’s different from performing calculations once someone’s already identified the mathematical structure. Same goes for spotting when a media claim requires statistical interpretation.

When mathematical study focuses on abstract procedures justified by theoretical elegance or usefulness ‘someday,’ students don’t develop analytical confidence. They never successfully apply frameworks to problems they actually care about. Mathematical identity forms around computational performance rather than problem-solving capability.

Traditional evaluation emphasizes computational accuracy and procedural fluency. Tests check whether students execute algorithms correctly. They don’t assess whether students recognize when mathematical reasoning applies, choose appropriate frameworks, or interpret results meaningfully. This creates incentive structures that reinforce procedural competency over analytical capability.

The Case for Authentic Application

Effective development of applied mathematical competency requires systematic exposure to authentic problem-solving contexts through educational approaches that position mathematical frameworks as tools for addressing genuine challenges rather than as abstract knowledge to master first and apply later.

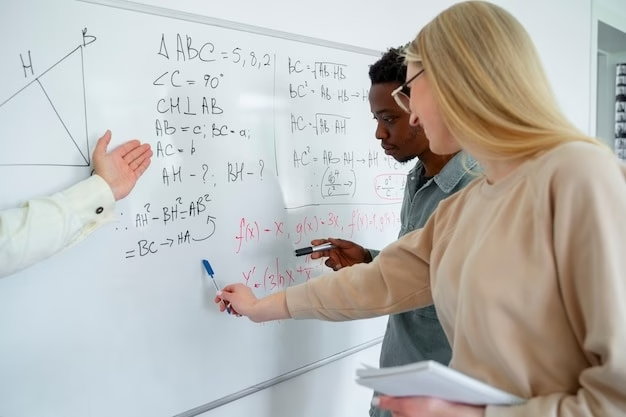

Project-based learning structures organize instruction around extended investigations of complex, open-ended problems requiring students to identify which mathematical frameworks apply. Authentic context provides both motivation and judgment-building experience of recognizing when particular competencies prove useful.

Some educational programs take this approach seriously. They build comprehensive curricula that develop real analytical skills. IB math applications and interpretation HL systematically develops statistical analysis, mathematical modeling, and practical problem-solving capabilities. These programs engage students with real-world scenarios such as financial mathematics, statistical interpretation, and mathematical investigation projects. Students tackle increasingly complex scenarios. This prepares them for careers requiring quantitative reasoning while building practical analytical skills essential for effective participation in data-driven decision-making across diverse professional environments and personal life contexts requiring mathematical literacy and evidence-based reasoning capabilities.

Effective approaches share common elements: positioning mathematical frameworks as problem-solving tools rather than ends in themselves, providing repeated practice recognizing when particular competencies apply to unfamiliar situations, requiring interpretation and communication rather than just computation, building analytical confidence through successful application experiences. These approaches integrate computational instruction with decision-making contexts, ensuring students develop both analytical judgment to recognize when mathematical reasoning applies and procedural fluency to execute appropriate techniques.

Look, we’ve all suffered through those contrived word problems about trains leaving stations at different speeds. Real scenarios don’t announce which formula to use—that’s the whole point.

Progressive Skill-Building Frameworks

Systematic development of applied mathematical competency follows a progressive structure from recognizing when mathematical frameworks might provide insight through selecting appropriate specific competencies to executing analysis and interpreting results meaningfully. Initial exercises focus on competency recognition: given a decision context, which analytical capability (statistical interpretation, probability reasoning, modeling, optimization) would provide the most value? Intermediate work develops framework selection: within statistical interpretation, would comparing distributions, testing relationships, or examining trends best address the question? Advanced application integrates multiple competencies as complex problems require probability reasoning about model predictions or optimization of outcomes under statistical uncertainty.

Authentic problem-solving scenarios accelerate capability development by engaging with actual decisions requiring mathematical reasoning. Unlike invented ‘word problems’ designed to practice specific techniques, authentic scenarios present genuine uncertainty about which approaches might work, what data prove relevant, and how to handle complications absent from textbook examples. Examples include evaluating competing claims about product effectiveness, comparing financial options with different risk profiles, analyzing how policy changes might affect various stakeholders, and improving efficiency of processes with multiple constraints.

Integration strategies connect mathematical frameworks to daily decision-making by establishing recognition habits. Actively identifying opportunities for mathematical reasoning in ordinary contexts—recognizing when news claims require statistical interpretation, when personal decisions involve optimization under constraints, when understanding situations demands modeling relationships—strengthens transfer. Reflecting on which competency proved useful builds meta-cognitive awareness enabling future recognition.

Building capability through graduated challenges provides achievable but meaningful success experiences. Systematic success progressively expands comfort with mathematical reasoning through repeated application to problems where frameworks genuinely help.

Cultivating Recognition and Transfer

The gap between possessing computational skills and applying them effectively centers on recognition—a meta-cognitive skill developed through deliberate reflection on successful applications. This capability determines whether someone can identify opportunities for mathematical reasoning in situations that don’t announce themselves as ‘math problems.’

Transfer depends on abstracting the deep structure of problems rather than surface features. Novices often fail to transfer because they categorize problems by surface content rather than by analytical structure. Expert mathematical reasoners recognize structural similarities across different contexts.

Deliberate reflection strengthens recognition and transfer. After applying mathematical reasoning to a decision, articulating which competency proved useful accelerates development. This practice builds a mental library of structural patterns that enhance recognition capabilities.

Sure, it sounds meta to think about thinking about math. But that’s exactly what separates people who freeze up from those who instinctively reach for the right analytical tool.

Recognition habits compound over time. Each successful application makes future recognition more likely. This positive feedback loop transforms mathematical reasoning from something done when explicitly prompted to a natural analytical habit applied spontaneously when situations warrant.

Recognition and transfer capabilities show how mathematical reasoning extends beyond executing procedures to include analytical judgment about when and how to apply frameworks. This reveals the distinction between knowing mathematics and thinking mathematically.

From Computation to Analytical Capability

Real mathematical competency isn’t about crunching numbers faster. It’s the shift from ‘Can I solve this equation?’ to something much more valuable: ‘Do I see when a situation needs mathematical thinking? Can I pick the right approach? And can I actually make sense of what the results tell me?’

This analytical capability matters because it lets you participate in data-driven decisions everywhere. Your career, personal choices, even civic engagement. Modern life constantly throws evidence-based claims at you. You’re always assessing risks when you don’t have complete information. You need to understand how complex systems behave and figure out how to use limited resources effectively.

Here’s the thing about ‘I’m not a math person.’ It usually reflects a gap between how we teach computation and what people actually need analytically. It’s not about mathematical inability.

We’d never brag about being illiterate, yet somehow mathematical illiteracy gets a pass. Most people already do informal statistical reasoning every day. Formal frameworks just make that intuitive reasoning more systematic and reliable.

Measuring real mathematical competency means looking beyond computational performance. Can someone recognize when a situation calls for mathematical reasoning? Do they apply it effectively without being told to? That’s what matters.

The ultimate test isn’t solving problems on command. It’s spotting opportunities for mathematical reasoning when nobody’s explicitly asking for it.

Mathematics as Applied Analytical Framework

Remember that calculator-without-context problem from traditional math class? The real world doesn’t announce when you need mathematical thinking. It just presents decisions where analytical frameworks provide better outcomes than intuition alone.

Applied mathematical reasoning represents not mastery of computational procedures but development of analytical capabilities—statistical interpretation, probability reasoning, modeling, and optimization thinking—that emerge through systematic engagement with authentic problems rather than abstract theoretical study.

Building genuine mathematical competency means learning to spot when analytical frameworks will help, knowing which ones fit the situation, and understanding what the results actually mean. This shift transforms mathematics from academic subject to practical capability.

The disconnect between computational instruction and practical needs creates an artificial barrier between ‘math people’ and everyone else. Mathematical reasoning becomes accessible when understood as systematic framework for decision-making—something everyone already does informally that becomes more powerful when developed deliberately.

The real measure isn’t whether you can solve equations on command. It’s whether you automatically think statistically when evaluating claims, probabilistically when assessing risks, systematically when modeling complex situations, and strategically when optimizing outcomes. That’s not being a ‘math person’—that’s just being analytically literate.